By Kevin Ferrara

Though the first two decades of his career were marked by fame, experimentation and a youthful joy in technical virtuosity, Walter Everett had only now and again shown flashes of the true extent of his gifts on the national stage. In truth he had spent the majority of his time since gaining fame rushing work out of his studio; conjuring too many rapid-fire vignettes and overnight monotypes to count. His work was always enjoyable and professional, he was that talented and proficient. But not even the finest talents can do timeless work under such constantly stressful and churning circumstances.

That changes beginning in 1921, a watershed year not only for him, but the illustration field as a whole. The magazine market had come out of a slump caused by the economics of the first World War and was flying high again. And now the top periodicals were starting to reward better work with the advent of new young stars such as Dean Cornwell and Norman Rockwell, both of whom created fully composed and finished paintings for their commercial clientele. In this suddenly reignited field Everett seems to have decided that it was time that he fulfill his potential and compete in the top echelon of illustrative art. To accomplish that, however, he had to slow down and reinvest in himself again as an Artist. He had to get back to drawing and dreaming. He had to treat his illustration work as Howard Pyle envisioned it; as a high destiny.*1 He even moved back to the Howard Pyle art colony in Wilmington to be alongside those stalwarts who had remained – like Frank Schnoover and Stanley Arthurs – who had kept the Pyle faith alive after his death.

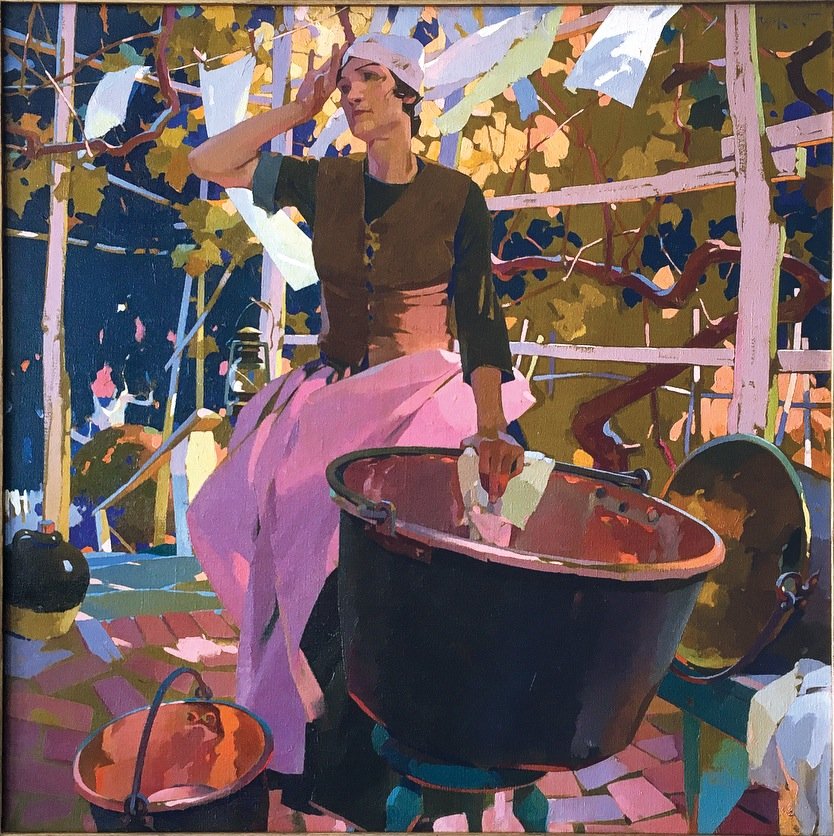

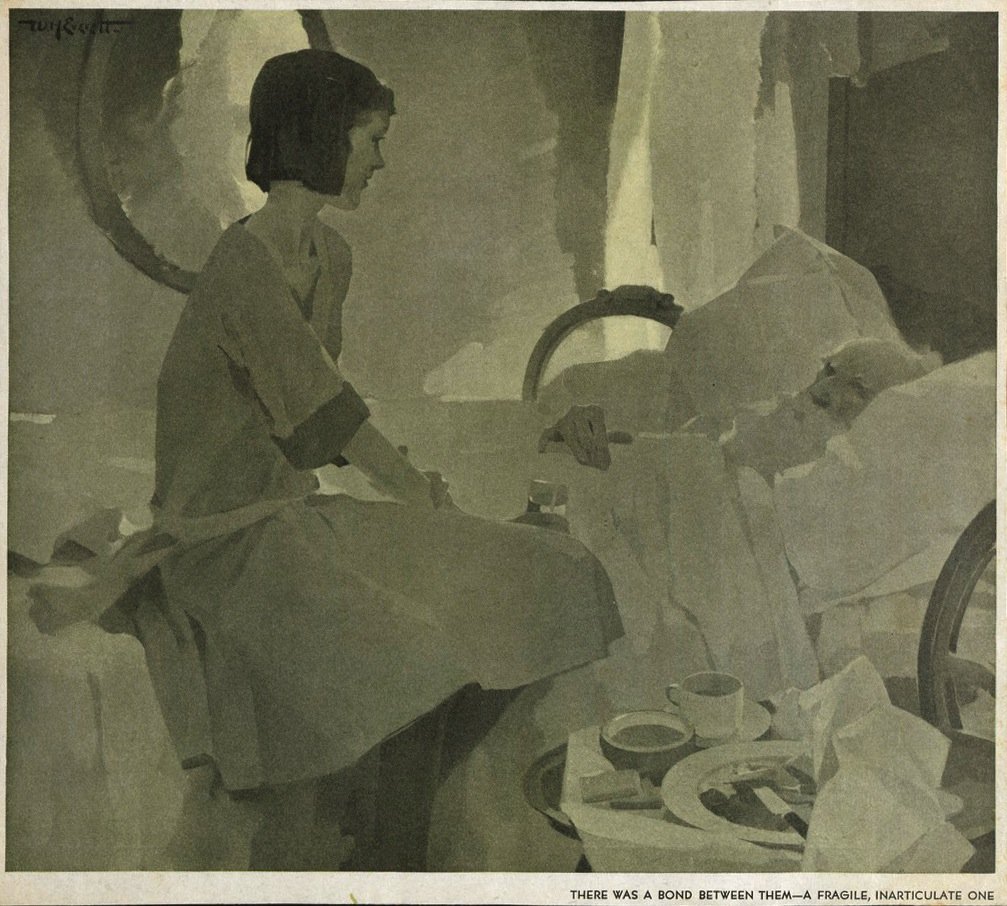

Thus, from the early 1920s until the end of his career in 1935 we get the mature and fascinating artist we all recognize today. Everett’s work undergoes a decisive change in character and quality. He makes fully composed easel pictures only, abandoning all the quick and tricky work that he had allowed to become his bread and butter in the prior era. His work becomes simultaneously deeper in poetic feeling and more meticulous in its craftsmanship. His influences so integrated they feel entirely backgrounded, as his own artistic ideals and personality take center stage.

He becomes more keenly aware of the “Total Effect” of the picture, and less concerned with mark-making for its own sake. He works through a period of dazzling showmanship into a quieter, more concise mode. His figures loom larger, his silhouettes get flatter, yet his pictures seem more spacious somehow.

He seems to have revisited Howard Pyle’s ideas and suddenly found new possibilities in them, new freedoms and inspiration. Howard Pyle taught that suggestion was the highest aspiration of art.*2 That less can mean more if it suggested more. So Everett began editing out anything from his work that could be suggested, clearing his work of the redundant and the lifeless. Which then left room for more suggestion. And so his work became broader, more silhouette-oriented and full of brilliance and aesthetic life.

He becomes increasingly concerned with pre-visualizing his compositions, both dreaming them over idle days purposely set aside, and then diligently outlining them in preparatory drawings which he traced off to his canvases.*3

He became more specific in his choices, more concerned with the judicious selection of elements for his pictures and the quality of the drawing. Everything was used to contribute to the overall pictorial idea. He becomes more diligent about his referencing and draftsmanship, and increasingly analytical in sculpting his forms, more apt to nail the complications of drapery and musculature rather than guess at it and disguise his guesses with brushwork bravado. He paid greater attention to expressive space division, and balance.

The result of all this was that Everett, like many of the great illustrators and imagists, developed a kind of aesthetic dreamworld all his own; hypnotic, strangely beautiful and instantly identifiable.

But Everett’s newfound dedication to his art had its downside as well. Dreams and deadlines rarely mix well. And as his career wore on into the 1930s, as he became widely talked about in art circles *4 and sought after by top editors *5 he also began having trouble meeting the demands of his profession. Stunning but unfinished canvases began piling up, some published, some not. He retreated into the hinterlands of Pennsylvania to a brother’s farm.

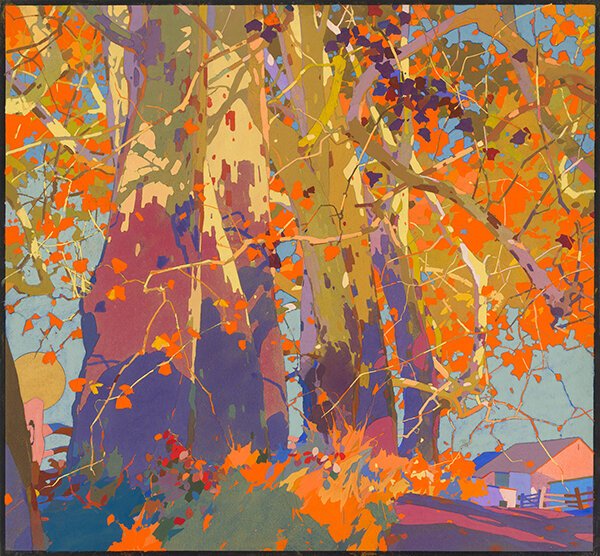

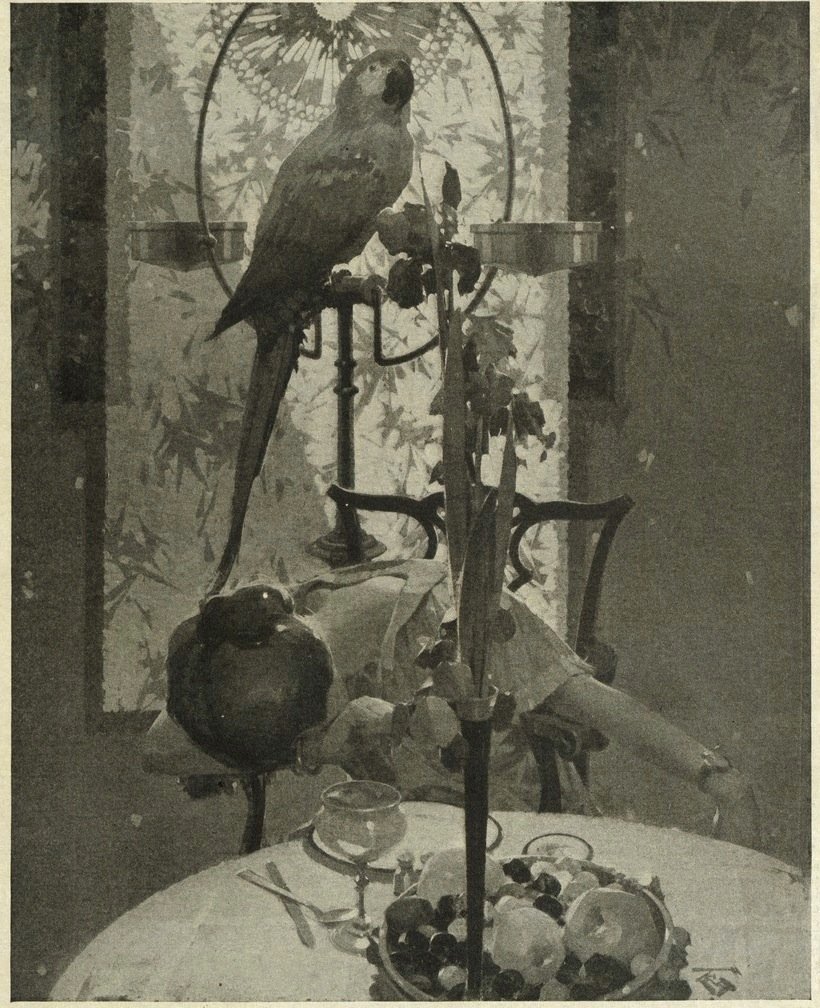

His output dwindled. But he kept dreaming. He loved nature. He painted bright poetic landscapes in watercolor, delicate visual haikus of flowers, stunning still lives. But with one last masterful set of images in 1935, his illustration career came to a halt.

Everett family lore has it that he made an attempt to switch to fine art gallery work around the same time he left the illustration field. But he was rebuffed; denied entry because, he was told, he was only a ‘mere illustrator’.*6

Only in his mid 50s, the great painter-illustrator Walter Everett essentially stopped being an artist. And began breaking down. In a fit of despair, frustration or insanity – probably all three - he set fire to the contents of his studio. He watched the bulk of his life’s work, even the bulk of his life’s meaning, burn to ashes at his own hands.

Everett continued being, but he was no longer the same. He was still a fascinating conversationalist, and a keen appreciator of nature, he still entertained visitors and had a wide circle of friends and gave a few local art lectures, but he no longer made much of anything except arrowheads, chipping, eventually, a boxful. He smoked too much, became dissipated, and disinterested in daily responsibilities. Eventually the smoking killed him. A quiet, sad end to a life that had long since gone quiet.

The epilogue to his story, however, is interesting. After his death, his son found on the dirt floor of his father’s barn a small pile of monotypes, drawings, sketches, tearsheets, paintings, and printer’s proofs that had been left unscathed, spared incineration at their creator’s hands during that feverish ‘bonfire of the vanities’ moment. Among these discovered remnants, by some miracle, were a handful of Walter Everett’s very greatest works.

“1. Richard Wayne Lykes. “Howard Pyle, Teacher of Illustration,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, July, 1956, 369.

2. Allen Tupper True. Unpublished Notebook; Notes Taken In the Class of Howard Pyle. August 15, 1904. Manuscript.

3. Benjamin and Jane Sperry Eisenstat, “Methods of the Masters: Walter Everett,” Step By Step Graphics, January, 1988, 109.

4. Henry C. Pitz. “Howard Pyle – Writer, Illustrator, Founder of the Brandywine School” 1975, 222

5. Henry C. Pitz, The Brandywine Tradition (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1968), 165.

6. Mark Everett. Private conversation with the author. New York City, Society of Illustrators, 2016.”