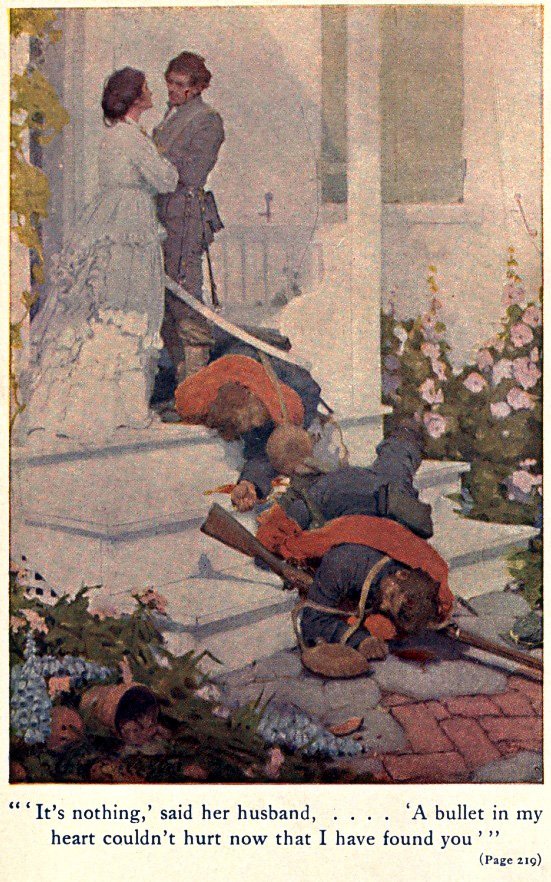

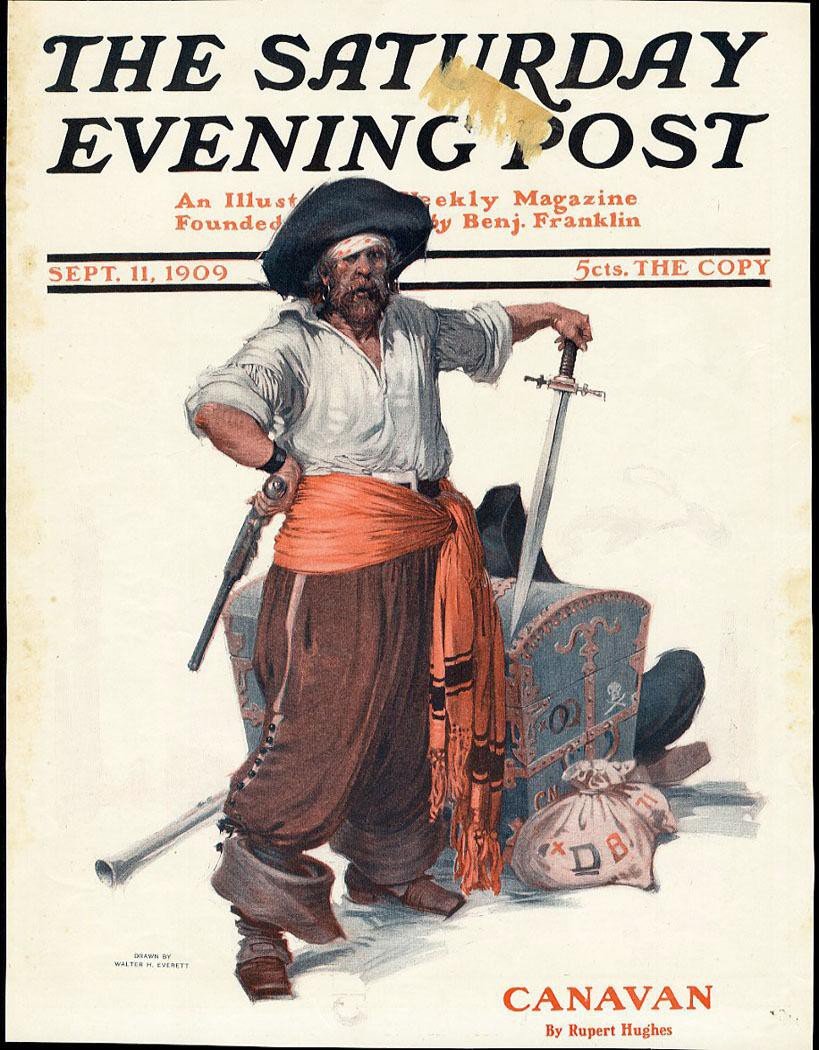

Walter Everett’s early professional work was as mercurial and interesting as he was. Whereas most illustrators kept at one style that relied on a single technique, Everett was adept at a host of different styles and seemingly any medium he turned his hand to. He produced professional works on deadline in oil, watercolor, gouache, tempera, charcoal, and pencil. It didn’t seem to matter what pigment or substrate he used, when he put his mind to it, every method yielded to his artistic will. He was that rare combination of born artist and born craftsman.

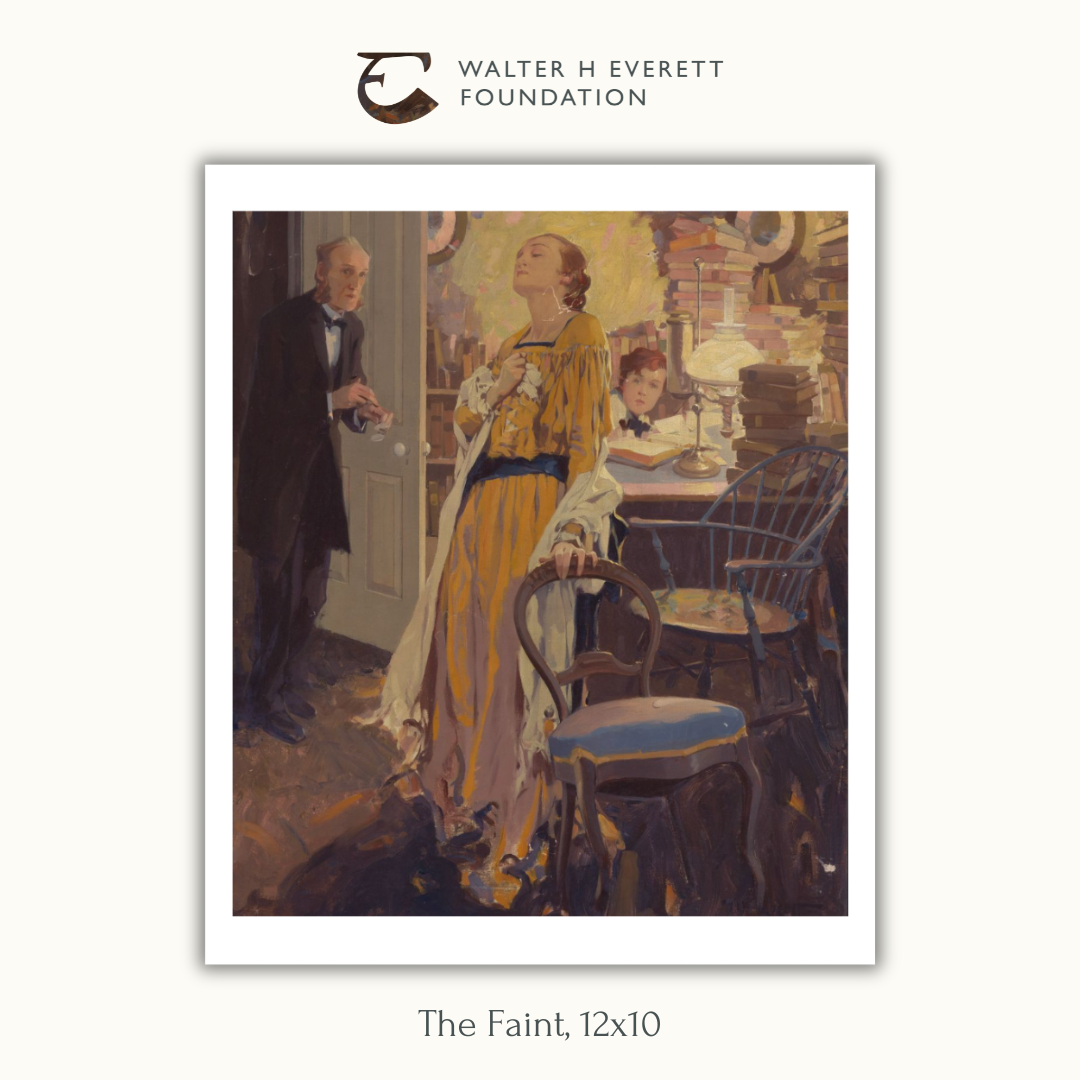

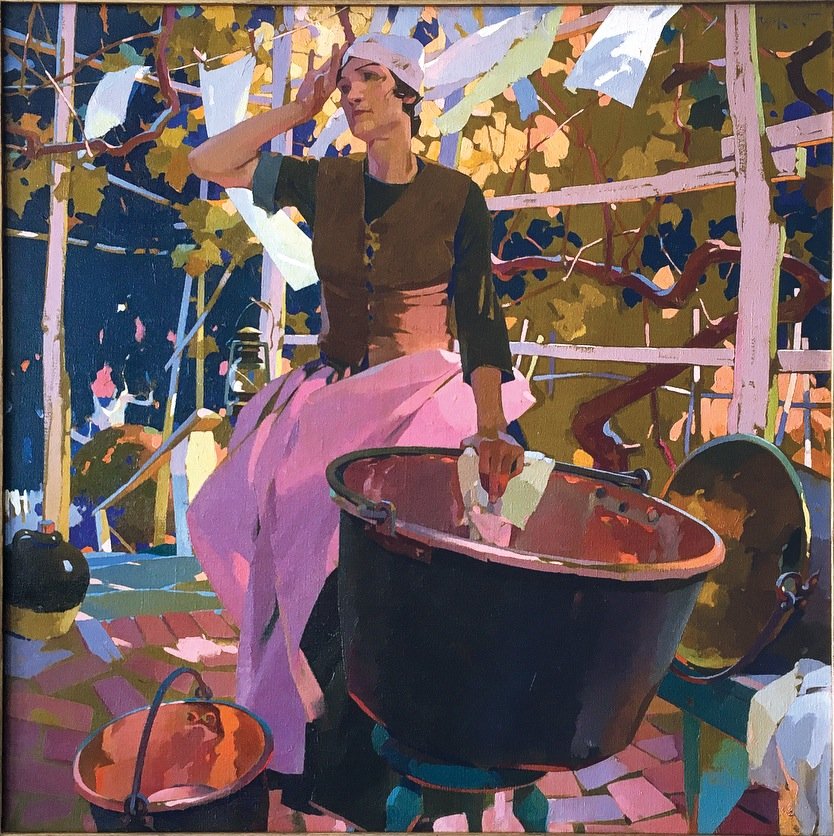

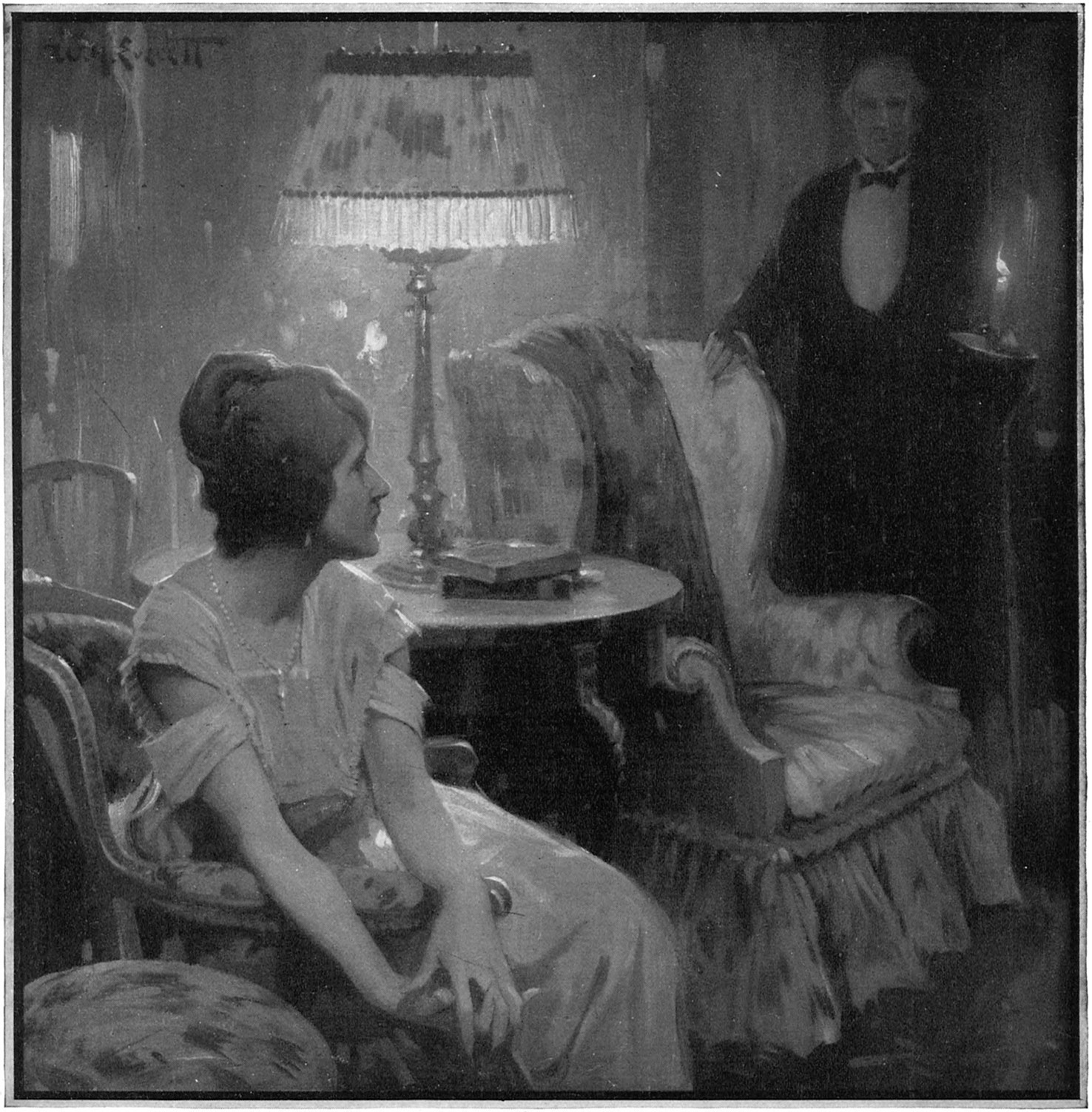

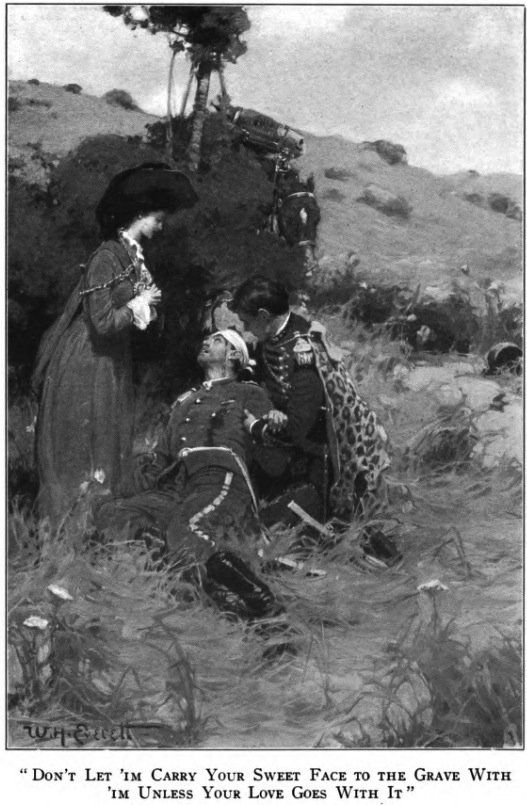

While thriving in the highly competitive illustration market, Everett constantly pushed his already formidable technical expertise. He hand-cut and shaped his painting brushes to ensure the quality and fidelity of his tools for those key moments of ‘action’ at his easel.5 Obsessed with the language of brushwork, he became a virtuoso of laying down in one go confident and descriptive paint strokes, creating work that feels as fresh as an impromptu performance, even on the poorly-printed page.

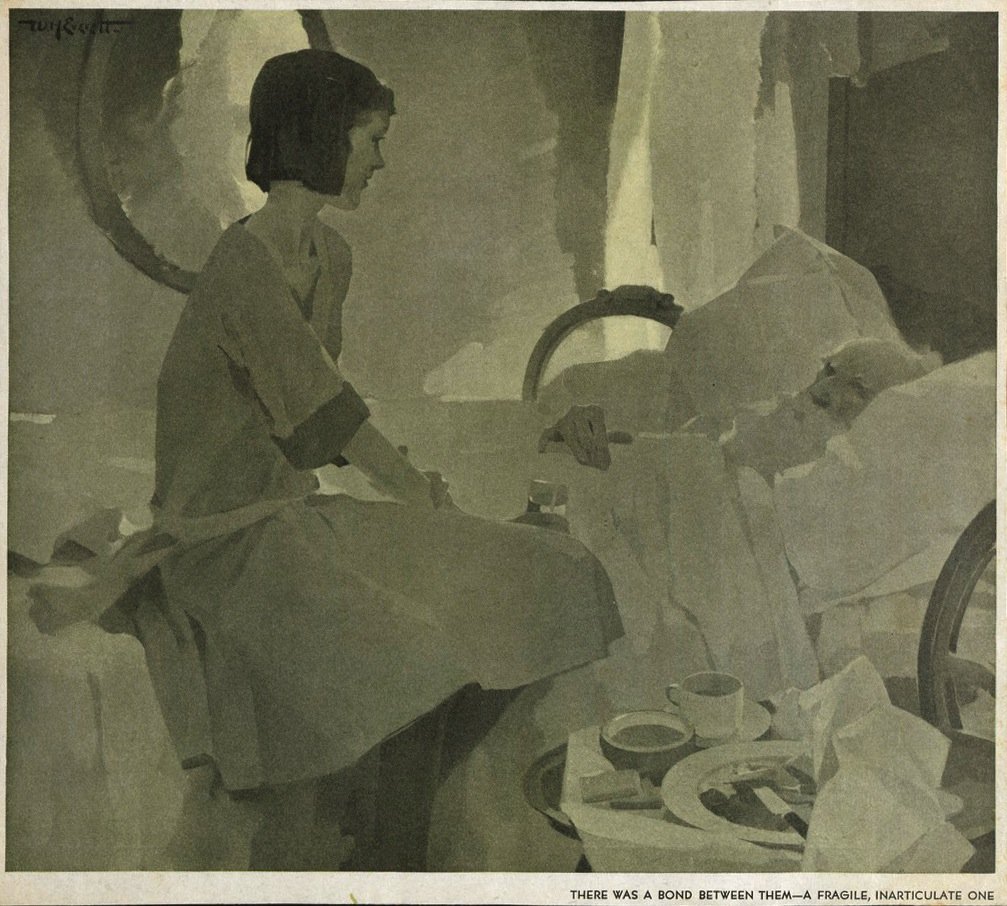

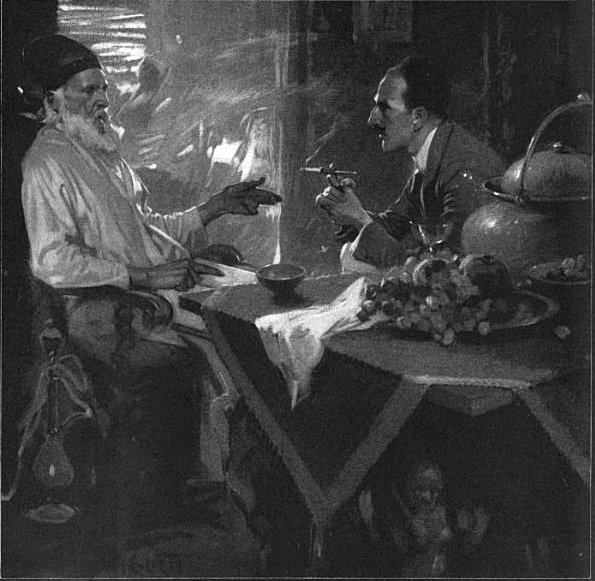

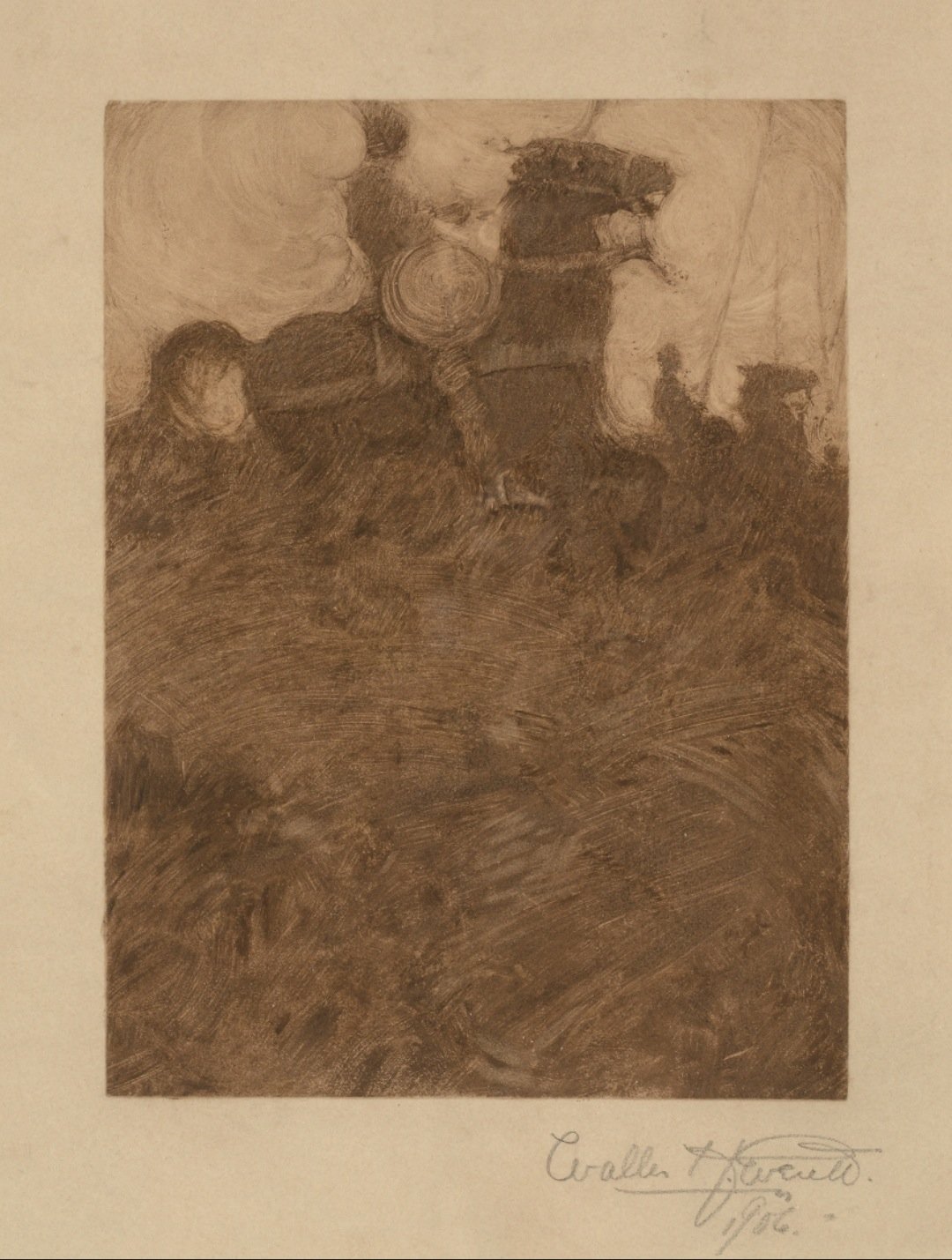

Everett exhibited his mastery most theatrically via monotype; a method of painting on glass in sepia and pulling off a print before the pigment dried. Everett may have been the only illustrator in the Pre-War period with the intense imaginative concentration, accuracy of drawing, and blazing speed to pull off this technique professionally. It was one of his calling cards, and his editors at Curtis publishing drew attention to it by crediting such illustrations ‘Monotype by Walter Everett.’

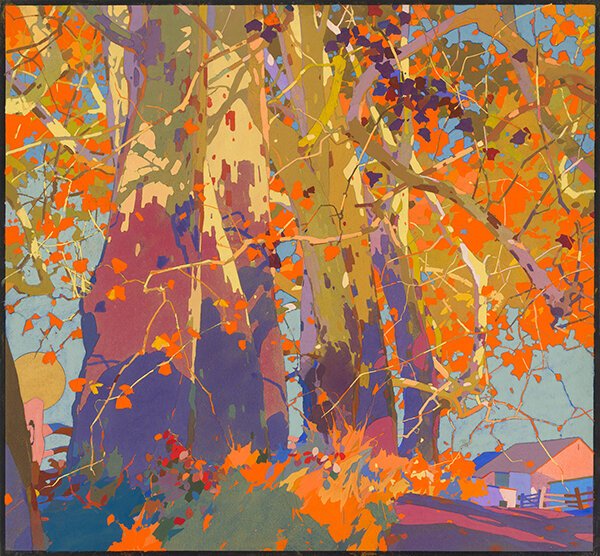

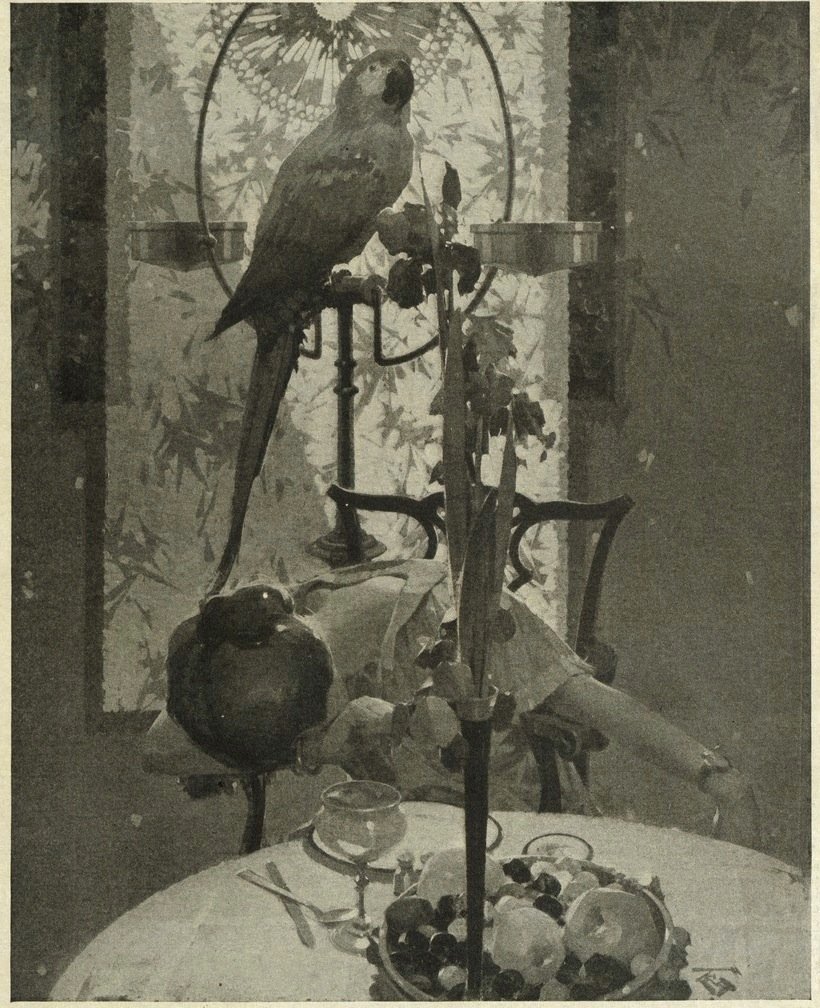

Clearly an avid museum and exhibition-goer, Everett was passionate about both the current state of the fine and decorative art world and its deep plumbing of art history. He had a voracious mind; appreciated and analyzed keenly. He saw all around him the world of modern culture and Art bursting with interesting new ideas worth pursuing. And Everett had no fear of experimenting with his Art in public to incorporate these heady au courant influences.

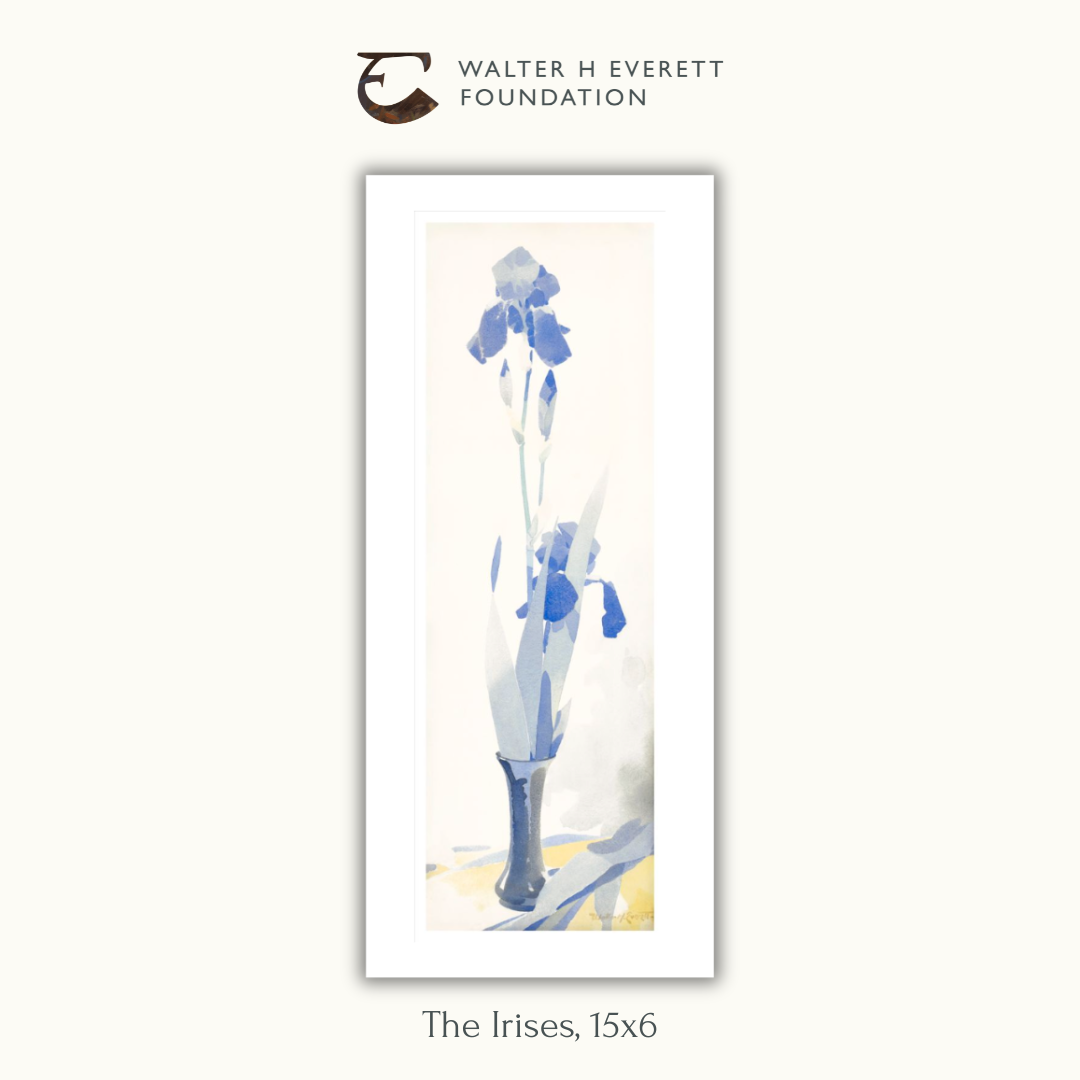

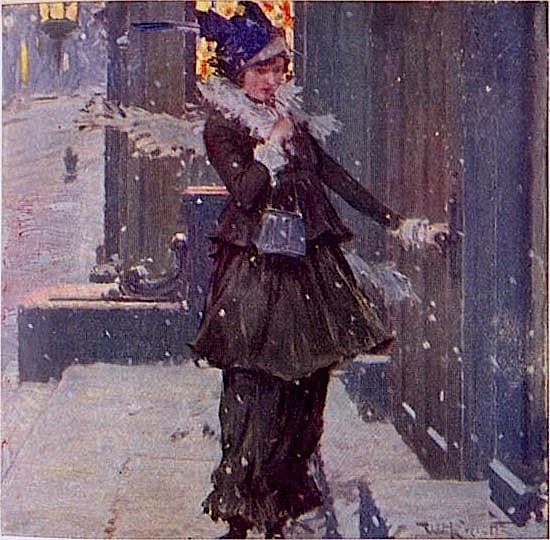

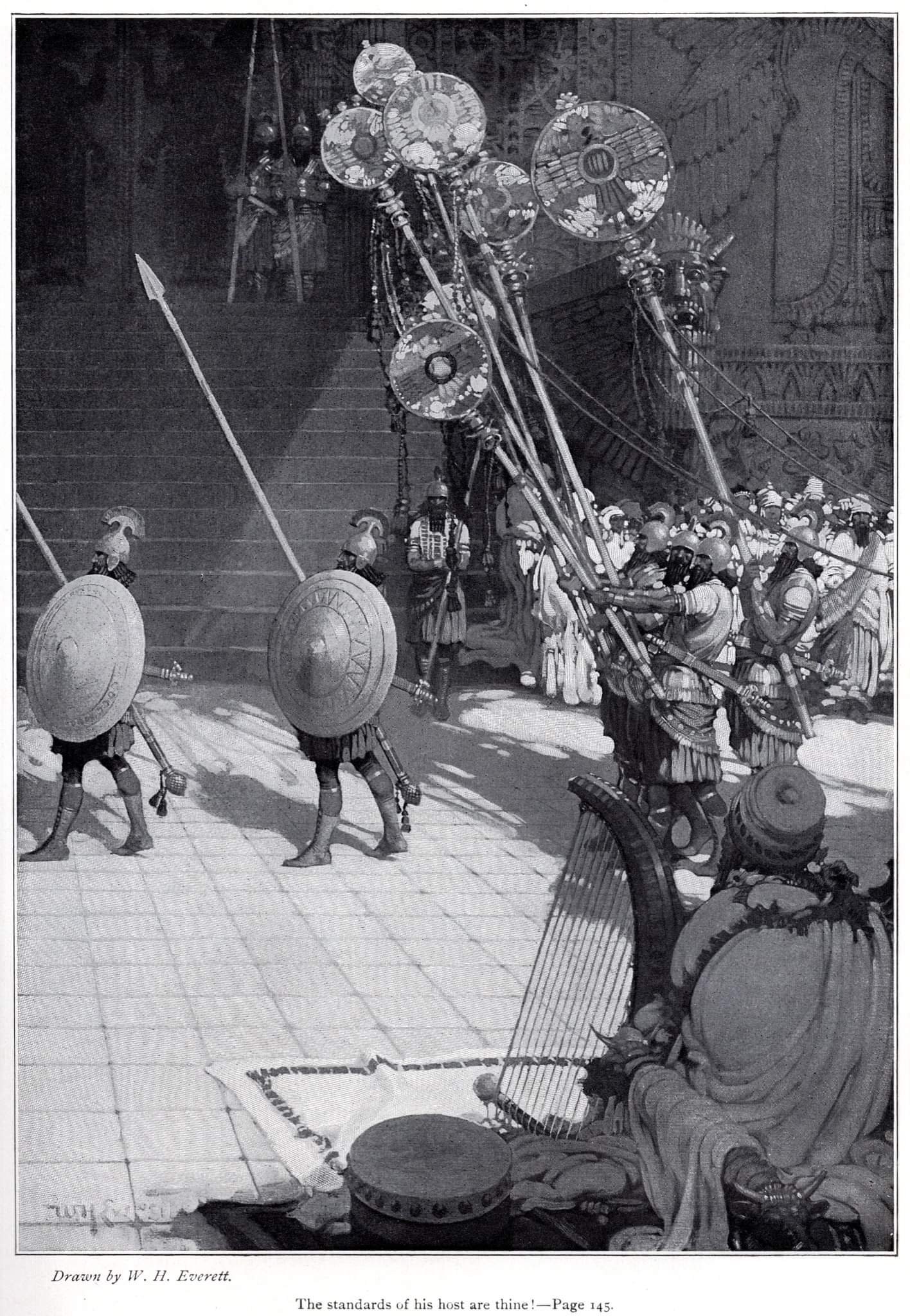

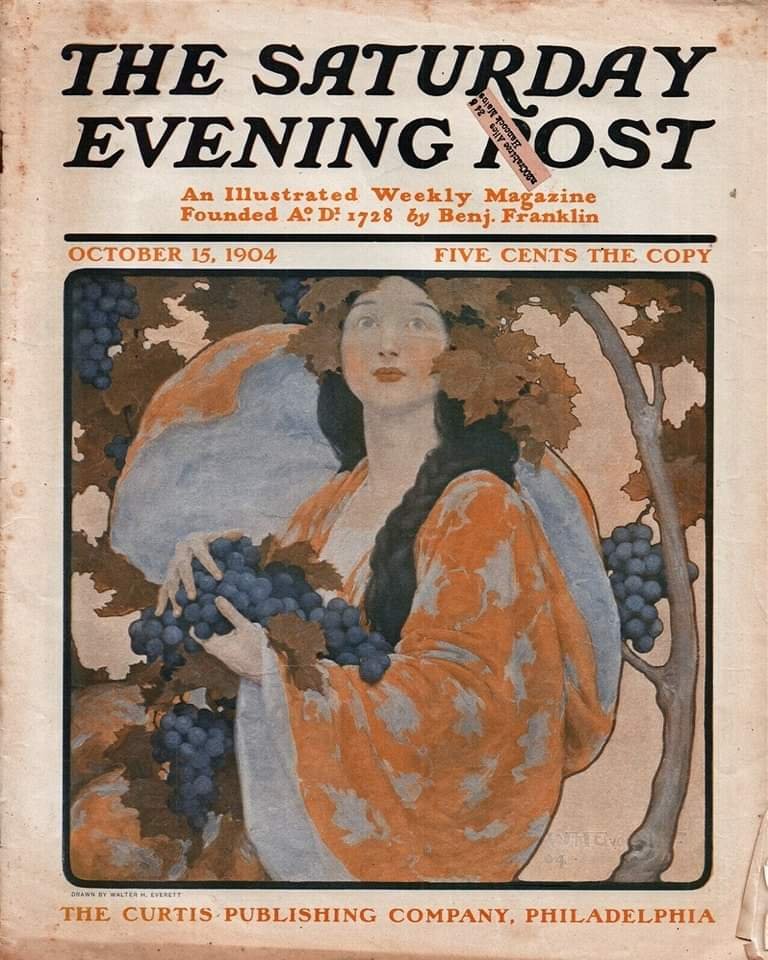

He created beautiful pieces in the turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau style. He crafted graphic posters. He adapted Assyrian motifs, Egyptian decorations, Japanese Screens, Stained Glass Windows, Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts, and Blackletter Calligraphy into otherwise naturalistic work. He learned the lessons of Impressionism and Tonalism, and developed his own brand of Cartooning.

Everett was acutely aware of the merit of other artists too, besides the work of his mentor. He was heavily influenced by the thick decorative painting and early modernist abstractions and patterning of Frank Brangywn and the striking brushstrokes and sparkling rendering of J.C. Leyendecker and Henry Reuterdahl.

Yet with all this outside content pouring into him, he integrated it all. He was one of the rare few who could incorporate a multitude of styles and artistic eras into his work without losing what was unique in himself.

Everett became a star in the illustration world at about the same time that his great mentor and teacher Howard Pyle unexpectedly passed away. Following in his mentor’s footsteps, while still at the height of his powers, Everett began a parallel teaching career at his alma mater PMSIA passing on Pyle’s principles.6 With his top-shelf training and experience – and his innate gift for inspiring young talent - he had much to give his students. And he molded many callow artists quite quickly into the next generation of illustration pros.

Much of what is known about Everett as both a character and a talent comes from the reports of his students during his teaching days. Anecdotes attest to his personal magnetism, his whimsical nature, his penchant for dreaming and flights of poetic fancy. Also his constant roiling creativity, which resulted in a somewhat brisk intolerance for the mundane and rote. Everett was quickly annoyed at the walled-in classroom setting for the teaching of Art. As an antidote, he would readily take his class on impromptu field trips to experience the wonderment of sketching from nature first hand; of course accompanied by his observant guidance. Just as Howard Pyle had done for he and his classmates years earlier.7

As an in-class demonstrator, even half a century later his students would attest to Everett’s astonishing facility with paintbrush and charcoal. A true virtuoso, he dazzled his pupils at the easel and drawing board with his visual memory, speed and accuracy. His top students – fired by not only the quality of their teacher but how quickly they were advancing in their own art - became fiercely loyal to him. And as word spread of Everett as the natural successor to Howard Pyle as the teacher of the very popular “Brandywine-style” Illustration, his classes grew and grew.

For PMSIA, having Everett around was a boon; registrations skyrocketed. But for Everett – famous, driven, and quirky - the responsibilities began adding up beyond a sum he was able to tolerate. Giving back was taking too much of him.

He left PMSIA, but briefly came back to academia to fill in at the Spring Garden Institute in New Jersey for a former student who had been called up in the World War One draft. But as the 1920s began, Everett clearly decided he needed to retrench as a creative force once and for all. He still periodically gave lectures on aspects of illustration art thereafter, but in the main he rededicated himself to being solely an artist.